Here’s something you might not know about me: for about 5 years I studied poop. Mouse poop; rat poop; human poop; you name it. It started when a researcher from the prestigious Rowett research institute came to talk to my undergraduate nutrition class about the microbiota; the collection of microorganisms that live (predominantly) in our large intestine. I then went on to do my honours research project and dissertation at the Rowett, studying, you guessed it: poop. For a while there, I was really into poop and guts and bugs. So much so that I pursued a PhD in the area, taught microbiology labs to undergraduate students, worshipped at the temple of Jeffrey Gordon, and even got my name on some papers (nerd stuff, more nerd stuff).

I was fairly certain that this would be my career trajectory - researching the interrelationship between the gut microbiome, diet, and the immune system. That is until my PhD supervisor went off the rails and I had to start my PhD research from scratch in a completely different area - cool story, maybe I’ll tell you about it some time. And despite being scarred for life about a career in academia, I have low-key maintained an interest in ‘gut health’ over the years.

So, it has been kind of wild to me, how this thing that I’ve studied, in quite literally microscopic detail, has become fetishised by everyone from wellness-industrial-complex-snake-oilmerchants all the way through to credible nutrition and health professionals.

Despite being purely a marketing term, with no scientific definition, the concept of ‘supercharging’ your microbiome has become buzzier than a blue bottle furiously flapping at a closed window. The global ‘digestive health’ market size was USD 48.4 billion in 2022, according to market.us. That market size is projected to grow to USD 104.4 billion by 2032. I want to devote more time and space to ‘gut health’ at some point because there’s a lot of dubious claims out there. But for now, I’d like to focus on one specific piece of advice for ‘supercharging your gut’: the recommendation to eat 30+ diverse plant foods per week (30+PPW).

This particular recommendation is all over Wellness Tok, and has been ‘reported’ in Stylist, Women’s Health, and (ofc) The Guardian. And, as with a lot of hot trends in nutrition, all roads lead to Tim Spector. It’s a familiar story; old school messages like eating 5-a-day and whole grains are tired and ‘outdated’. Eating 30+PPW is cool and much more ‘scientific’ as Stylist claimed, despite evidence showing that following dietary current guidelines does, in fact, lead to a pretty diverse gut microbiota. The premise of 30+PPW is that in order to maximise the diversity of our gut bugs, we should aim to eat 30 different types of plants each week. Each different type of plant will, advocates claim, feed a different ‘type’ of bacteria, leading to higher microbial diversity. And, in fairness, studies do point to many disease states having lower microbial diversity, although whether making a gut microbiome ‘more diverse’, can reverse disease, or reduce risk of disease (and by what extent) are still, I think, questions scientists are parsing out.

So where did the 30 plants recommendation come from? And, is it credible?

Here’s where things get interesting - at least if you’re nerdy about the gut microbiota, which we have established, I am. Advocates of the 30+PPW trend will point to a pretty nifty study, formerly called the American Gut Project (AGP), and now known as The Microsetta Initiative. Microsetta is a not-for-profit, crowdsourced, citizen-scientist project that aims to collate the world’s largest library of human gut, oral, and skin microbes, or, at least their DNA. The project is headed up by Professor Rob Knight, who has been hot shit in the study of the microbiota at least since I was a PhD student.

The project was established to catalogue the huge diversity of the human gut microbiome 1 and is probably one of the most ambitious and far-reaching studies of the microbiome, ever. By recruiting ‘citizen-scientists’ and crowdsourcing funding through sites like Indiegogo, researchers can reach far more study participants than if they just went down the usual route of getting government or industry funding. It also means that the data set is open access; any researcher, anywhere in the world can run analysis on the data set and potentially make new and interesting contributions to the field.

So what do these citizen-scientists have to do? Well, each participant pays USD 99 to receive a testing kit, (which is significantly cheaper than ZOE btw). Participants are then asked to collect a faecal, oral, or skin swab sample and are given instructions to send it back to the researchers. They may also complete a voluntary questionnaire, answering questions on health status, disease history, lifestyle and diet. Once they’ve returned their sample, participants will receive a report detailing what bacteria are living in their sample (i.e. in the gut, mouth, or on the skin) and how that compares to everyone else who has participated in the study. Although the study began in the US, researchers now have 32,000 samples from people in over 80 countries.

This project is seriously fucking cool.

Through this work, researchers have been able to document a much wider variety of microbes living in our bodies than they have through previous smaller studies. The more samples scientists can collect, the closer they get to mapping the boundaries of the microbial communities that live synergistically with humans.

What does all of this have to do with 30-plants-a-week?

Well, in 2018, when it was still known as the American Gut Project, Knight’s team published a paper in mSystem, a journal of the American Association for Microbiology. It was the first publication from this citizen-science project, reporting on associations from the first 10, 000 or so samples. This in and of itself was a big deal, providing a proof-of-concept for citizen-science that wasn’t funded by industry, or tied to elusive academic grants.

Among other things, researchers found that, compared to people who eat less than 10 different types of plant foods per week, those who eat 30 or more, have a greater variety of microbes in their guts. The variety of plants was more predictive of microbial diversity than dietary labels like ‘vegan’ or ‘vegetarian’. Instead for these groups they found a more specific bacterial ‘signature’ or ‘fingerprint’.

It’s important to note that the researchers only looked at the diversity of microbes that had a very specific function in the gut, which is to produce chemicals called short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like butyrate which are considered to protect against colorectal cancer. A key point to consider here is that this study found diversity in terms of bacteria that perform this specific function, not diversity as a whole. That’s not an insignificant finding - but it’s different from ‘30+PPW is the gold standard, fuck your 5-a-day!’.

Regardless, ‘experts’ have jumped on the idea that you should eat 30+PPW for ‘optimal’ gut health. But this interpretation of the evidence is, in my opinion, REACHING.

While the AGP study is really interesting, and a really important contribution to the field. It’s not perfect.

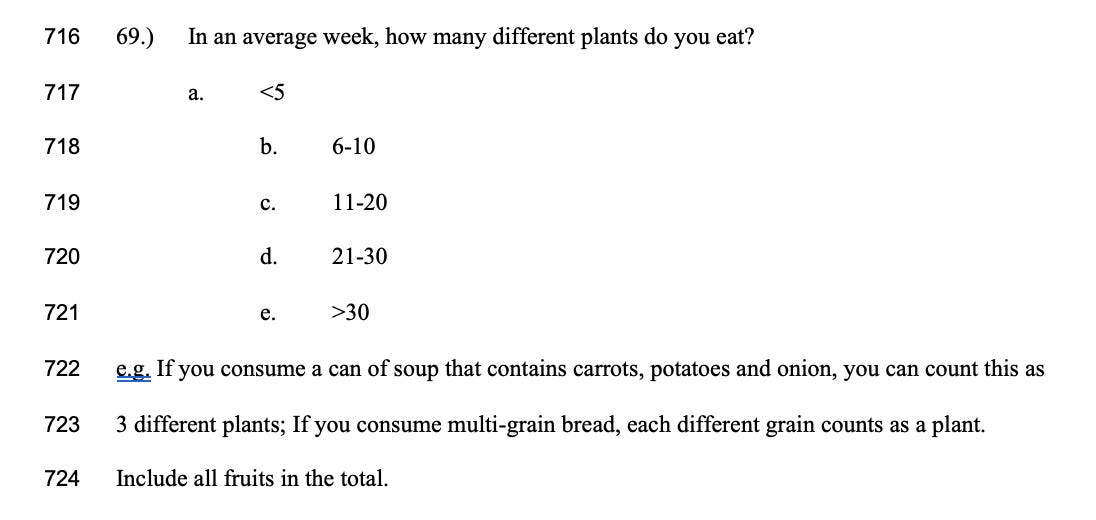

First of all, I think there are issues with how they measured what exactly counts as a ‘plant’. Remember that this is a citizen-science project? That means that participants were responsible for reporting their own diet using a food-frequency questionnaire.

Here’s the question used to determine if people were eating 30+ plants:

You can see the problem right? The response to this question is subjective and vulnerable to bias. Memory recall bias is a common issue in nutrition research - put it this way, I ate lunch ten minutes ago and I don’t think I could accurately recall how many plants were in it! It’s hard to guesstimate how many plants you eat in a week, especially if you didn’t prepare the food yourself. These reports are also subject to what researchers call ‘social desirability’ bias - we want to report that we eat more plants than we did because, well, it looks good!

There’s also no guidelines given in terms of how much of a plant needs to be consumed for it to ‘count’. What if my can of soup contains spices and herbs? Do they ‘count’? They are plants afterall. Tim Spector would say yes (we’ll come back to this), but the question is so vague that inevitably different people will have interpreted this differently. And although the question asks how many different plants someone eats in a week, there’s nothing to stop people counting the carrots in their soup and the carrots with the roast dinner as two different plants.

Another salient point to pull out of this study is that the researchers compared what they called the ‘extremes’ of dietary plant intake, meaning they compared people who ate 10 or less plant foods per week, with 30-or-more plant foods per week. They didn’t look at the diversity of the microbiome with 15 or 20 plant foods per week. We therefore don’t know if we might have had similar diversity with slightly less plant foods than with the more ‘extreme’ 30 plants. In other words, how do we know that there isn’t a ‘ceiling’ effect reached at a lower threshold if that wasn’t the question that was asked? Or indeed, whether there are diminishing returns over a certain number of plants?

One final consideration is that the AGP study did not measure health outcomes. It did not find that eating 30+PPW is the golden number for optimal ‘gut health’, nor did it find that 30+PPW would reduce risk of disease. Remember that it’s a cross-sectional study - it’s designed to describe the microbiome and find potential associations with diet. As far as I’m aware, no study has asked people to eat 30+PPW, and then measured if this lowers their risk of disease or, indeed, improves their ‘gut health’ in meaningful, measurable ways.

I’m not contesting that dietary variety, particularly from plants, contributes to a more varied microbiome. What I am contesting though, is the uncritical way this study has been reported and incorporated into recommendations, particularly when there’s also a profit motivation. Microbial ‘diversity’ or ‘variety’ has become a high water-mark for gut health girlies - but scientists still can’t define or characterise exactly what constitutes a ‘diverse’ gut microbiome.

To put it crudely (and I’m sorry micro nerds) imagine a car factory that is filled with mechanics and engineers - you could have thousands of workers, but if all they’re trained to do is fit the wheels on a car, who is working on the engine, transmission, and electronics? We can have species richness in the microbiome, but that doesn’t always translate to functional diversity. And to complicate things further, the ‘best’ kind of diversity may be different for different people. And this is what we saw in the AGP study - there were lots of butyrate producers there, which on balance is a positive thing. But butyrate production is only ONE of the functions of the microbiome, which also synthesises vitamins, transport nutrients, and metabolise medications, among many, many other ‘jobs’. Work from Jeffrey Gordon, and Rob Knight who leads the AGP (dream team), showed that you can have a community of gut microbes which is diverse in terms of the members who are present, but they all essentially do the same thing.

Look, for a whole bunch of people, the advice to eat more plants isn’t that big a deal. But we have to remember that AGP/ Microsetta is not a ‘testing’ kit designed to make specific recommendations and it cannot predict how changes to the diet will affect any given individual. Which is why blanket recommendations to eat a certain number of plants, without any kind of caveat, could be harmful. While, generally speaking, increasing the number of plants, and therefore the amount and type of fibre you’re eating can have beneficial effects, for others it can lead to urgency, diarrhoea, constipation, gas, bloating, and pain - especially if you have irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). For others with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), fibre may need to be completely removed from the diet for a period of time when people are experiencing a flare in their symptoms.

And it’s not just me who worries about the impact of this trend. I asked digestive health dietitian Samina Qureshi her thoughts on the imperative to eat 30+PPW

‘My initial thoughts about the 30 plant-per-week trend is that it's a great way to increase fiber consumption and gain the benefits of eating more plant-based foods. However, I do have my concerns for people who may struggle with perfectionism, disordered eating, or an eating disorder. Often these trends can get blown out of hand when people don't make space for balance on their plate.’

While Samina highlights that things other than just fruits and veg, like whoegrains, nuts, seeds, and traditional or cultural foods, can be supportive of digestive health, not everyone will respond to this diktat the same way.

‘As a digestive health dietitian, I also have concerns about specific populations trying this trend. If you struggle with IBS and are on the low FODMAP diet be sure to consult with your dietitian for appropriate low FODMAP plant-based options that won't trigger an IBS flare’ says Samina.

She continues: ‘I’m also concerned about those who struggle with chronic constipation. Adding more plant-based foods can be helpful after you have resolved your constipation and found balance with eating patterns and macronutrients that support proper digestion. If you add too many plant-based foods too fast without resolving constipation you can make constipation worse causing more stomach pain, bloating, gas, and discomfort. People with active IBD flares may not respond well to all types of fiber so this trend would not necessarily be appropriate for them if they don't know how to modify the fiber texture and source to suit their needs.’

For people who are neurodivergent, experience health anxiety or who have a history of disordered eating, I wonder about the impact of having to meet specific target numbers, and the worry and stress of not meeting those numbers. And what about folks who, because of sensory processing differences, disability, or trauma, have a limited diet where they physically cannot eat 30 different foods, let alone 30 different plants? And what about folks who are food insecure or financially vulnerable whose priority is just having enough food to eat at all? By foregrounding ‘gut health’, and quibbling over the ‘optimal’ number of plants one should consume each week, we lose sight of bigger social and structural determinants of health which inevitably have a bigger bearing on disease risk.

Alright free list - this is where we’re leaving you! To read more about how this trend is leading to exploitative marketing that evades statutory food labelling regulations to shift products, and how the idea that we need ‘just a pinch’ of a food for it to ‘count’ is misleading, upgrade your subscription now! You’ll also get some solid pointers from Samina about how we can look after our digestive health, without stressing about numbers!

As with all good nutrition trends, the food industry has gobbled up 30+PPW. Holland and Barrett recently launched a convoluted ‘plant point’ system to sell their new range of own brand products. ‘Studies have shown that eating 30 different plant foods a week can play a positive role in leading a healthy lifestyle’ boasts their senior nutritionist Alex Glover. Ehhh, that’s study, singular, Alex mate. He goes on to say ‘participants who ate a broader range of plants had more diverse gut microbiomes – which play a huge part in human health and disease’. But I don’t think we’re at a point in our understanding of the microbiome where we can quantify the effect that it has on overall health and wellbeing. Do we know it’s important - for sure! Does it play a huge part in human health and disease? I don’t think we know that. Indeed, a 2015 critical review highlighted ‘the need for high-quality, large-scale human dietary intervention studies’ in this area, as well as some of the methodological concerns of this type of research.

Similarly, Marks and Spencer’s are jumping on the 30+PPW bandwagon, albeit more subtly than their ZOE collaboration. Although they launched their Plant Kitchen range five years ago, they have recently introduced two new products that are more ‘plant forward’ than their typical offering: More Than Meatballs, and More Than Mince. The products represent a shift from more traditional vegan alternatives, based on soy or wheat proteins (i.e. seitan), towards recipes that use more vegetables. The More Than Meatballs packaging boasts that it is made with over 10 different plant-based ingredients, a very clear nod to the 30+PPW imperative.

Of these products, M&S’s head of development for Plant Kitchen, James (no surname given), said ‘These vegetable-based protein products are setting the standard for what 2024 is going to be about: vegan products that are high in protein, high in fibre, low in salt and more beneficial to your body than meat’.

But here’s the thing, in order to meet their a-priori goal of hitting a high-protein, high-fibre food – a combination that generally isn’t found naturally in foods other than nuts and seeds – they’ve had to use a variety of fibres and proteins extracted from foods. The ingredients list contains things like psyllium husk, citrus fibre, pea fibre, apple fibre, and bamboo fibre. Not only are these ultra-processed foods (who has bamboo fibre lying around their kitchen?), but they’re not great for folks with sensitive digestive systems - in other words, the exact people who are looking to improve their gut health and who might be attracted to the ‘10 different plants’ marketing. While again, eating a more diverse diet isn’t inherently bad, I find the way that industry responds to these trends exploitative. Side note: I bought the meatballs by accident, and they were boggin’, as we might say in Scotland.

I’m curious to see how this plays out for the food industry; unlike claims pertaining to how many portions of fruit or vegetables are contained in a product (i.e. 1 serving contains 2 of your 5-a-day) – which are clearly defined and regulated – claims about ‘number of plants’ is a convenient loophole for industry which can give the impression that a product needs more of your nutritional needs than it actually does. Saying a product contains 5 plant ‘ingredients’, ‘varieties’ or ‘points’ could give the impression that it contains 5/5 portions of fruit or vegetables per day. When in reality, the quantities of each ingredient could be so small, that it doesn’t even make up even 1 portion of your 5-a-day (which needs to be a minimum of 80g of most fruits or vegetables to count).

Which brings me full circle, back to our old mate Tim, who claims that it’s not the quantity of a plant-ingredient that is important, but that even the smallest amounts will do. Tim includes things like a pinch of a herb or a teaspoon of a spice as one of your 30+PPW. Which leads me to believe that maybe he doesn’t have a solid grasp on how the microbiota function; to establish or grow the number of a particular strain or species of bacteria, you need to give them enough substrate, or food, to eat. The AGP study didn’t establish the quantity of a plant-based ingredient that would support the growth of beneficial bacteria, otherwise known as a prebiotic effect. This confusion pours over into recommendations related to the 30+PPW recommendation with no standardised approach to how it’s applied - Tim suggests that even a pinch counts, a dietitian recommends a ‘substantial portion’, and Holland and Barrett suggest it’s something more like your 5-a-day.

Although any given plant food may only ‘count’ as one plant point, we have to remember that a food like oats, carrots, or, an apple are each made up of hundreds of different chemical components, including different kinds of fibre and phytochemicals, that each provide a substrate for different types of bacteria. This isn't a 1 food, 1 bacteria situation, and as long as you aren’t experiencing any troubling digestive symptoms, you don’t need to sweat it. And if you are, maybe don’t get your advice from Stylist?

As a starting point, Samina has this to offer: ‘Try focusing on staying hydrated throughout the day, getting adequate rest, developing a more consistent meal and snack routine, practicing deep diaphragmatic breathing to help with stress management, and including a source of carbohydrates, fat, protein, and color in your meals throughout the week. And remember, no amount of probiotics, prebiotics, or supplements are going to magically cure your gut health. When it comes to supporting your digestive health, sticking to the basics of balanced nutrition will go a long way!’

Getting variety in our diet might be great for those of us who have access to the resources to do so, but it’s far from essential for supporting digestive health, and there’s nothing to say that 30 plants is the be all, end all.

There is no study that I can point to that proves that eating 30+PPW will reduce your risk of a specific disease by a quantifiable amount. There have been no randomised control studies that feed people 30+PPW and then measure biomarkers for disease risk. There are no longer-term epidemiological studies that compare people who are eating 30+PPW, and less than 30 plants per week, and compare their long-term health outcomes. This is just ONE, pretty cool, but inconclusive study.

ICYMI last week: Dear Laura...Help! My Kid is Too Distracted to Eat.

While the microbiota refers to the living organisms in and on our body (of which there are an estimated 39 trillion), the microbiome refers to the genetic capacity of the microbiota ↩